- Home

- Richard Jefferies

Landscape with Figures

Landscape with Figures Read online

Richard Jefferies

LANDSCAPE WITH FIGURES: SELECTED PROSE WRITINGS

Edited and with an Introduction and Preface by

RICHARD MABEY

Contents

Preface to New Edition

Note on the Text

Introduction

LANDSCAPE WITH FIGURES:

SELECTED PROSE WRITINGS

Part One:

Writings on Agricultural and Social Affairs (1872–80)

Wiltshire Labourers

The Labourer’s Daily Life

The Gamekeeper at Home: The Man Himself – His House, and Tools

Village Architecture: The Cottage Preacher – Cottage Society – The Shepherd – Events of the Village Year

Hamlet Folk

Minute Cultivation – A Silver Mine

The Amateur Poacher: Oby and His System – The Moucher’s Calendar

The Hunting Picture: Its Defects and Difficulties

Part Two:

Natural History Writings (1878–86)

Rooks Returning to Roost

Wind-Anemones – The Fish Pond

A Brook – a London Trout

Mind Under Water

The Modern Thames

The Water-Colley

Trees About Town

Nightingales

The Hovering of the Kestrel

Out of Doors in February

Haunts of the Lapwing: Winter

Part Three:

Late Essays (1882–7)

Notes on Landscape Painting

Walks in the Wheat-fields

Nature and Books

Absence of Design in Nature – The Prodigality of Nature and Niggardliness of Man

One of the New Voters

After the County Franchise

Shooting Poachers

Primrose Gold in Our Village

Hours of Spring

My Old Village

Bibliography

PENGUIN CLASSICS

LANDSCAPE WITH FIGURES: SELECTED PROSE WRITINGS

RICHARD JEFFERIES (1848–87) was probably the most imaginative and certainly the least conventional of country writers. He never worked the land and did not always live in the countryside, but in his articles and essays he single-handedly created the modern idea of English ‘nature writing’.

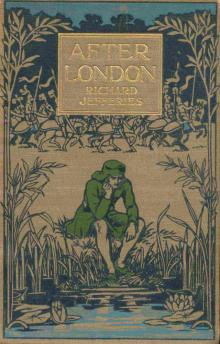

He wrote an astonishing amount in his short life, including novels (most famously Bevis and the hugely influential post-apocalypse novel After London), an autobiography, The Story of My Heart, and numerous essays on the English countryside, both about the people who lived and worked there and about its animals and plants.

After an education at Oxford, RICHARD MABEY worked as a lecturer in social studies, then as a senior editor at Penguin Books. He became a full-time writer in 1974 and is the author of some thirty books, including Weeds: How Vagabond Plants Gatecrashed Civilisation and Changed the Way We Think About Nature (2010); Whistling in the Dark: In Pursuit of the Nightingale (1993), winner of the East Anglia Book Award, 2010, in a revised version entitled The Barley Bird: Notes on a Suffolk Nightingale; Beechcombings: The Narratives of Trees (2007); the ground-breaking and best-selling Flora Britannica (1996), winner of a National Book Award; and Glibert White, which won the Whitbread Biography Award in 1986. His recent memoir, Nature Cure (2005), which describes how reconnecting with the wild helped him break free from debilitating depression, was short-listed for three major literary awards: the Whitbread, the Ondaatje, and the J. R. Ackerley prizes. He writes for the Guardian, New Statesman and Granta, and contributes frequently to BBC radio. He has written a personal column in BBC Wildlife magazine since 1986, and was made a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature in 2011.

Preface to New Edition

Richard Jefferies died of tuberculosis in 1887, aged thirty-eight. In a writing life of little more than twenty years, he showed signs of becoming a literary polymath, publishing nine works of fiction and more than 450 essays and pieces of journalism. They range from a tone poem on ‘The Lions in Trafalgar Square’, through slight ‘nature notes’ and political brickbats on the misdemeanours of agricultural labourers, to metaphysical meditations on human perception. What links them is a nagging, inquisitive and, just occasionally, toxic curiosity about what, in the great scheme of things, was the relationship between human beings, nature and the land.

It’s not surprising that in Jefferies’ own breakneck career this passion moved through distinct phases. It began in his teens, with strictly journalistic and often deeply conservative surveys of the worlds of farming and gamekeeping, shifted to sharper enquiries into natural history, and concluded with a kind of inclusive synthesis, in which human nature, the ‘more-than-human world’, and the deep mysteries of consciousness all become part of a single ‘field-play’. Jefferies was trying urgently to work out who he was, as a displaced, rootless, professional peerer, being rapidly invaded by one of the more destructive manifestations of nature.

Jefferies first perched on my shoulder when I was about twelve years old, and has lurked (not always enjoyably) in the shadows ever since. What fascinates me is how Jefferies’ phases – ‘movements’, if you like – have been echoed both in my own life, and in the shifting focus of public interest. When I first came across him, I was an adolescent nature-romantic, inclined to solitariness. His numinous landscape writing touched something quite deep and undefined in me, and I aped his style shamelessly in school essays. When I was sixteen I won a prize for one of these pastiches, and chose Jefferies’ ‘spiritual autobiography’, The Story of My Heart, as my reward. It is a measure of how tastes change that the staff in charge of prizes had never heard of either it or its author, and suspected from the title that it was some cheap novelette. So it had to be vetted. They might just as well not have bothered. I found it incomprehensible once I’d been presented with the thin volume, and it still seems to me a faintly distasteful piece of pre-New Age self-indulgence.

Half a century on, the reading public is more aware of Jefferies, especially his special contribution to what is now known as ‘nature writing’, as distinct from ‘natural history writing’. I find I’m constantly discovering new aspects of him here as well. His instinctive grasp of ecology was always obvious. Even in his most despairing moments, he understood the individual human’s inseparability from the rest of creation, however indifferent creation was to him. But a sharpening of our contemporary interest in what, precisely, these links are has helped highlight what a precocious observer Jefferies was. He was a kind of hedge-scientist, reasoning through analogy, forging explanations by the application of reason and intuition to acute observation. It’s not a respectable scientific mode these days, but it creates a space where human imagination can meet the constantly evolving, experimenting pool of life. Jefferies was surprisingly modern in his ideas about perception, too. He was aware of the dangerous subjectivity – but also creativity – of the senses, of how cultural context, psychological preconception, even pure optical illusion, shape the way nature appears to us. The mutability of the perceived world – and of evolving life itself – were, in the end, a single phenomenon to him.

I chose the selection in Selected Prose (which was originally published as Landscape with Figures: An Anthology of Richard Jefferies’s Prose) in the early nineteen-eighties, when interest in Jefferies reflected current political and social worries, and focused on his writings about the uneasy relations between country and city, the future of democracy, the idea of the ‘organic’ community. I suspect that this aspect of his work is likely to come to the fore again, and I hope that its inclusion here, alongside his more immediately popular nature writing, will help give a more balanced view of an unusual, troubled, but always relevant, writer.

>

Richard Mabey

Norfolk, 2012

Note on the Text

Rather than follow a strictly chronological order, I have arranged the pieces that follow in a way that may help illustrate the development of Jefferies’ thinking. I have also put them into three rough groups (agricultural and social affairs; natural history; general, philosophical essays) that correspond to the three main phases of his career, though there are of course overlaps both in time and subject matter.

Introduction

Nearly a century after his death it is still hard to say exactly what kind of writer Richard Jefferies was. On the strength of the few of his books that are still widely read – The Gamekeeper at Home, Nature Near London, Wildlife in a Southern County – he is recognized as probably the most imaginative observer of the natural world of his century. More generally he is regarded as a ‘country’ writer, and that will certainly do as a rough description of his working territory. But in any less literal sense it is a definition which immediately begs the most important question about his work, for there is nothing conventionally rural about Jefferies. He was never a land-worker and for a good deal of his career did not even live in the countryside. His writing rarely has the qualities of peace, quiet and timelessness that are supposed to characterize ‘rustic’ literature. He can appear, sometimes inside a single piece of writing, as a small-town journalist, a romantic radical, a social historian and an apologist for the landowning class. The closer he is read the more the major concern of his work appears to be an implicit questioning of what a ‘country writer’ is, an exploration of the relationships that are possible between a reflective outsider, marginal in all senses to the real business of the land, and the hard imperatives of life in the fields. To what extent is the ‘countryside’ not just a fact of geography and a place of work but an emblem of a whole range of social and spiritual values? And if there are intangible estates, who are the rightful inheritors?

The more urban our society becomes, the more relevant these questions seem, and it is no wonder that in some quarters Jefferies’ life has been mythological. In the most telling version – out of the Golden Age by the Romantics – chance brings together this visionary spirit, born of ancient English farming stock, and the last remnants of an unblemished and untroubled countryside. The reality was rather different. Jefferies was raised on an unsuccessful smallholding in a county where, just twenty years before, labourers had fought pitched battles with the yeoman farmers. He began writing during the great agricultural depression of the 1870s, and died, after years of suffering, when he was only thirty-eight, from tuberculosis.

We have to remember this history when reading Jefferies. But equally, I believe, we have to remember the myths. A feature of his writing is the way it taps and exposes our preconceptions about country life. In his huge output of essays and articles almost all our current beliefs and worries are prefigured.

In this anthology I have tried to sketch the development of Jefferies’ thinking on social, political and ecological matters as it is expressed in these essays and articles. (His fiction is outside the scope of this collection, and is in any case less interesting.) The sheer range of his output was formidable. In a working life of not much more than twenty years he published nine novels and ten volumes of non-fiction. Another ten collections appeared posthumously. His non-fiction works were mostly quarried from more than 450 essays and articles he contributed to some thirty different publications, from the Live Stock Journal to the Pall Mall Gazette. He would write with equal willingness (though not always equal facility) technical pieces for the farming press, improving articles for home encyclopedias and propaganda for Tory journals. In the high-circulation tabloids he pioneered the ‘country diary’, and the distinctive discursive style he developed is still echoed in a score of local newspapers. In almost the same breath, it seems, he was able to retreat into mystical reveries of the kind typified by The Story of My Heart, and then burst into radical sermonizing. Partly he wrote as any freelance will, what he was paid to write by his editors; yet the shifts also happened unprompted, as Jefferies revised yet again his opinion of where he belonged in the rural scheme of things.

Although Jefferies’ willingness to change his mind has sometimes been used as a reason for dismissing his work as trivial or untrustworthy, it is refreshing to find this kind of flexibility in ‘country’ writing. For a motif that is so important in English literature, the countryside has been portrayed from a notoriously narrow set of views, and only exceptionally by those who worked on it themselves. Permanence and peace, consequently, have been sighted more often than change and conflict, and natural harmony (though this is often illusory too) taken to include social harmony. At worst, the indigenous human has been absorbed completely into the natural landscape as another kind of sturdy and contented ruminant. This is a damaging process, and as Raymond Williams has pointed out, ‘A fault can then occur in the whole ordering of the mind. Defence of a “vanishing countryside” … can become deeply confused with that defence of the old rural order which is in any case being expressed by the landlords, the rentiers, and their literary sympathizers.’*

Although an excess of pastoral naïvety has produced, understandably, a suspicion of onlookers’ and outsiders’ versions of the rural experience, this can lead to another kind of bias, in which all such views are dismissed as aesthetic indulgences. Yet the cycles of birth, death, harvest and renewal which characterize the agricultural and natural worlds have been a powerful source of symbols at every level in our culture, even for those who do not live close to them. And there is a sense in which a settled rural landscape, whose pattern of fields, farms and churches embodies the history of a hundred generations, is a vision of Eden, no matter what temptation and toil lie hidden behind it.

There has been no shortage of writers willing to ignore this problem of perspective and depict the countryside in simple black or white terms. Jefferies’ accomplishment was to portray it in all shades with an equal vehemence and within the compass of a single working life. Although in the short term his versatility can look like shallowness or opportunism, in the context of his whole work it seems more like a rare kind of honesty.

The central character in what Jefferies once called ‘The Field-Play’ is the land-worker himself. The shift in the way he is depicted – from laggard to victim to hero – is the most striking expression of the movement of Jefferies’ thinking. Even his physical characteristics are viewed in different ways. In the early 1870s he is described as a rather badly designed machine. Ten years later he is being explicitly compared to the form of a classical sculpture.

Typically, it was with a shrewd, unflattering sketch of the Wiltshire labourer (to-day it would rank as an exposé) that Jefferies pushed his writing before a national audience in 1872. The Agricultural Labourers’ Union had been formed just two years earlier and there was mounting concern amongst landowners about its likely impact on the farm. Jefferies was working on the North Wilts Herald at the time, and realized that he was well placed to make an entry into the debate. He had a lifetime’s experience of observing agricultural affairs, an adaptable and persuasive style, and enough ambition not to be averse to saying what his readers wanted to hear. So he composed the first of his now celebrated letters to The Times on the life and habits of the Wiltshire labourer, and in particular his uncouthness, laziness and more than adequate wages. It was by any standards a callous piece, written with apparent objectivity but in fact with a calculated disdain that at times reduces the worker to little more than a beast of burden:

As a man, he is usually strongly built, broad-shouldered, and massive in frame, but his appearance is spoilt by the clumsiness of his walk and the want of grace in his movements … The labourer’s muscle is that of a cart-horse, his motions lumbering and slow. His style of walk is caused by following the plough in early childhood, when the weak limbs find it a hard labour to pull the heavy nailed boots from the thick clay soil. Ever afterwards he walks as

if it were an exertion to lift his legs.

Jefferies was wearing his contempt on his sleeve, of course; but when he returned to the subject in the Manchester Guardian thirteen years later, it is hard to credit that it is the same man writing. Even the title of the piece (like those of many of his later essays) has a new subtlety, being less a description of what was to come than a frame of reference within which to read it; ‘One of the New Voters’ had little to do with voting or party loyalties but a great deal, implicitly, with the human right to the franchise. It recounted with meticulous detail and controlled anger a day in the life of Roger the reaper. Although he is still an abstraction, not a person, Roger is an altogether more real and sympathetic character than his predecessors. No longer an intemperate idler, but a man tied to long hours of dispiriting work without the capital or political power to find a way out, he none the less keeps his own private culture intact. Jefferies describes a scene in a pub after the day’s work is over.

You can smell the tobacco and see the ale; you cannot see the indefinite power which holds men there – the magnetism of company and conversation. Their conversation, not your conversation; not the last book, the last play; not saloon conversation; but theirs – talk in which neither you nor any one of your condition could really join. To us there would seem nothing at all in that conversation, vapid and subjectless; to them it means much. We have not been through the same circumstances: our day has been differently spent, and the same words have therefore a varying value. Certain it is, that it is conversation that takes men to the public-house. Had Roger been a horse he would have hastened to borrow some food, and, having eaten that, would have cast himself at once upon his rude bed. Not being an animal, though his life and work were animal, he went with his friends to talk.

Bevis: The Story of a Boy

Bevis: The Story of a Boy After London; Or, Wild England

After London; Or, Wild England Landscape with Figures

Landscape with Figures After London

After London