- Home

- Richard Jefferies

Landscape with Figures Page 2

Landscape with Figures Read online

Page 2

This was a remarkable recognition from a man who just a few years earlier had seen nothing but vacant faces amongst the labouring class. But what really lifts this essay above the level of ephemeral social comment is that Jefferies sets it in the context of the great drama of the harvest, in which toil, sunshine, beer and butterflies, cornfield weeds and the staff of life, were mixed together in perplexing contradiction.

The golden harvest is the first scene; the golden wheat, glorious under the summer sun. Bright poppies flower in its depths, and convolvulus climbs the stalks. Butterflies float slowly over the yellow surface as they might over a lake of colour. To linger by it, to visit it day by day, and even to watch the sunset by it, and see it pale under the changing light, is a delight to the thoughtful mind. There is so much in the wheat, there are books of meditation in it, it is dear to the heart. Behind these beautiful aspects comes the reality of human labour – hours upon hours of heat and strain; there comes the reality of a rude life, and in the end little enough of gain. The wheat is beautiful, but human life is labour.

The central paradox of rural life has never been more plainly put. In another intense late essay, ‘Walks in the Wheat-fields’ (1887), Jefferies likens the blinding, desperate gathering-in of the harvest to ‘gold fever … The whole village lived in the field … yet they seemed but a handful buried in the tunnels of the golden mine …’ The double meaning of ‘living in’ here is very forceful; at the beginning of the piece he compares the shape of a grain of wheat to an embryo or ‘a tiny man or woman … settled to slumber’. In the wheat-field, he suggests, ‘Transubstantiation is a fact …’

In his last years Jefferies was increasingly preoccupied with the paradoxes that emerged when men lived close to nature. They seemed trapped in one way by their physical and biological needs, and in another by their sensibilities. If the ritual of harvest was paradoxical, so was all labour, which, depending on where you stood, could seem an act of nature or necessity, dignity or slavery. So, for that matter, was nature itself, which could be simultaneously cruel and beautiful. Jefferies’ concern with these ambiguities was in part a reflection of his own uncertain social position, as a man who had devoted his life to the expression of rural life, but who had no real role in it himself. He found no solutions to this enigma; but as he explores some of its more practical ramifications – could villages be centres of social change as well as social stability, for instance? what were the respective rights of owners, workers and tourists over the land? – his mixed feelings of exclusion and concern come increasingly close to our modern attitudes towards the countryside.

Richard Jefferies seemed destined to be a displaced person from childhood. He was born into a declining smallholding at Coate near Swindon in 1848. Although he was later to idealize both Coate and his father (who appears as the splendid, doomed figure of farmer Iden in the novel Amaryllis at the Fair, 1887) it does not seem to have been an especially happy household. A description of Coate in a letter from Jefferies’ father has a bitterness whose roots, one suspects, reach back to a time before Richard began upgrading his literary address to ‘Coate Farm’:

How he could think of describing Coate as such a pleasant place and deceive so I could not imagine, in fact nothing scarcely he mentions is in Coate proper only the proper one was not a pleasant one Snodshill was the name on my Waggon and cart, he styled in Coate Farm it was not worthy of the name of Farm it was not Forty Acres of Land.*

When he was four years old, Richard was sent away from Snodshill to live with his aunt in Sydenham. He stayed there for five years, visiting his parents for just one month’s holiday a year. When he was nine he returned home, but was quickly despatched to a succession of private schools in Swindon. Shunted about as if he were already a misfit, it is no wonder that he developed into a moody and solitary adolescent. He began reading Rabelais and the Greek Classics and spent long days roaming about Marlborough Forest. He had no taste for farm-work, and his father used to point with disgust to ‘our Dick poking about in them hedges’. When he was sixteen Richard ran away from home with his cousin, first to France and then to Liverpool, where he was found by the police and sent back to Swindon.

This habit of escape into fantasy or romantic adventure (it was later to become a characteristic of his fiction) must have been aggravated by the real-life decline of Coate. In 1865 the smallholding was badly hit by the cattle plague that was sweeping across southern England, and a short while later fourteen acres had to be sold off. Richard had left school for good by this time, and in 1866 started work in Swindon on a new Conservative paper, the North Wilts Herald. He was employed as a jack-of-all-trades reporter and proof-reader, but seemed to spend a good deal of his time composing short stories for the paper. They were a collection of orthodox Victorian vignettes of thwarted love, murder and historical romance, mannered in tone and coloured by antiquarian and classical references.* Although they are of no real literary value, they may have been useful to Jefferies as a way of testing and exercising his imaginative powers.

The next few years brought further frustrations and more elaborate retreats. In 1868 he began to be vaguely ill and had to leave his job on the Herald. In 1870 he took a long recuperative holiday in Brussels. He was extravagantly delighted by the women, the fashions, the manners, the sophistication of it all, and from letters to his aunt it is clear what he was beginning to think of the philistinism of Wiltshire society.

But circumstances forced him to return there in 1871, and to a situation that must have seemed even less congenial than when he had left. With the farm collapsing around them his parents resented his idleness and irresponsibility. He had no job and no money. He was able to sell a few articles to his old newspaper, but they were not enough, and he had to pawn his gun. His life began to slip into an anxious, hand-to-mouth existence that has more in common with the stereotype of the urban freelance than with a supposed ‘son of the soil’. He started novels, but was repeatedly diverted by a procession of psychosomatic illnesses. He wrote a play, and a dull and derivative memoir on the family of his prospective member of Parliament, Ambrose Goddard. The most unusual projects in this period were two pamphlets: the self-explanatory Reporting, Editing and Authorship: Practical Hints for Beginners, and Jack Brass, Emperor of England. This was a right-wing broadsheet that ridiculed what Jefferies saw as the dangers of populism.

… Educate! educate! educate! Teach every one to rely on their own judgement, so as to destroy the faith in authority, and lead to a confidence in their own reason, the surest method of seduction …

It was a heavy-handed satire, and though it may not have been intended very seriously, Jefferies was to remember it with embarrassment in later years.

But by this stage he had already made a more substantial political and literary debut with his letters to The Times on the subject of the Wiltshire labourer. It is important to remember the context in which these appeared. Agricultural problems of one kind or another had been central issues in British politics for much of the nineteenth century. But the land-workers themselves had been given sparse attention. And though they had been impoverished by the cumulative effects of farm mechanization, wage and rent levels, and the appropriation of the commonlands, their own protests had been sporadic and ineffectual. Then in 1870 Joseph Arch and some of his fellow-workers gathered together illicitly in their Warwickshire village and formed the Agricultural Labourers’ Union.

This was a new development in the countryside, and raised new anxieties amongst landowners. The rioting and rick-burning of the 1820s had fitted into a familiar stereotype of peasant behaviour, and had been comparatively easily contained. But organization was a different matter, and seemed to introduce an ominously urban challenge to the rural order and, by implication, to the social fabric of the nation which rested on it.

Jefferies’ hybrid background may have helped him understand these worries better than most, and it was the sense of moral affront sounded in his letters that won him sympathy from t

he landowners. The correspondence became the subject of an editorial in The Times, and Jefferies was soon offered more journalistic work in the same vein. Over the next few years he wrote copiously on rural and agricultural affairs for journals such as Fraser’s Magazine and the Live Stock Journal. Collectively these pieces are more informed and compassionate than the Times letters. Jefferies sympathizes with the sufferings of the labourers and their families, but believed that many of their habitual responses to trouble – particularly their reluctance to accept responsibility for their own fate – simply made matters worse. Wage demands alienated the farmers, who were their natural patrons and allies. Drink led to the kind of family break-ups described in ‘John Smith’s Shanty’ (1874). The only certain remedies were hard work and self-discipline.

This has been a perennial theme in Conservative philosophy, and there are times when Jefferies’ recommendations have a decidedly modern ring, as, for instance, in ‘The Labourer’s Daily Life’ (1874): ‘The sense of [home] ownership engenders a pride in the place, and all his better feelings are called into play.’ Yet even at this early stage, Jefferies’ conservatism has a liberal edge, and anticipates the libertarian, self-help politics of his later years. He speaks out in favour of allotments, libraries, cottage hospitals, women’s institutes and other mutual associations as means towards parish independence. And he begins to suggest that the farm and the village – the basic units of rural life – owed their survival and strength not so much to some immemorial order but precisely to their capacity to incorporate change and new ideas into a well-tried framework.

The increasing amount of work Jefferies was doing for London-based journals encouraged him to move to Surbiton in 1877, when he was twenty-eight years of age. Rather to his surprise he enjoyed London, discovering in it not only many unexpectedly green corners, but an exciting quality of movement and vivacity. As Claude Monet was to do in his paintings of Leicester Square and Westminster Bridge, Jefferies saw the rush of traffic and the play of streetlights almost as if they were natural events. In ‘The Lions in Trafalgar Square’ even the people are absorbed:

At summer noontide, when the day surrounds us and it is bright light even in the shadow, I like to stand by one of the lions and yield to the old feeling. The sunshine glows on the dusky creature, as it seems, not on the surface but under the skin, as if it came up from out of the limb. The roar of the rolling wheels sinks and becomes distant as the sound of a waterfall when dreams are coming. All abundant life is smoothed and levelled, the abruptness of the individuals lost in the flowing current like separate flowers drawn along in a border, like music heard so far off that the notes are molten and the theme only remains.

‘Lions’, like most of the London essays, was written during a later phase of Jefferies’ life. Perhaps because of his uncertainty about his own social role, he rarely wrote about his current circumstances, but about what he had just left behind. In Swindon, much of his work was concerned with the fantasy world of his adolescence. In Surbiton he is remembering his life at Coate, albeit in a rather idealized form.

The pieces that were to make up his first fully-fledged non-fiction work, The Gamekeeper at Home, were amongst these reminiscences, and were initially published in serial form in the Pall Mall Gazette between December 1877 and Spring 1878. It is of some significance that Jefferies chose as his subjects ‘the master’s man’ and the practical business of policing a sporting estate. The game laws were a crucial instrument for expressing and maintaining the class structure of the nineteenth-century countryside. Although poaching was an economic necessity for many families, it was also an act of defiance against the presumptions of landowners. They, for their part, often viewed the taking of wild animals from their land as a more fundamental breach of their ‘natural’ rights than outright stealing.

Jefferies doesn’t challenge this assumption in The Gamekeeper at Home. In a chapter on the keeper’s enemies, for instance, he moves smoothly from weasels, stoats and magpies to ‘semi-bohemian trespassers’, boys picking sloes and old women gathering firewood. ‘… how is the keeper to be certain,’ he argues, ‘that if the opportunity offered these gentry would not pounce upon a rabbit or anything else?’

This strand in Jefferies’ writing reaches a kind of culmination in Hodge and His Masters. This collection of portraits of the rural middle class – speculators, solicitors, landowners, parsons – was serialized in the London Standard between 1878 and 1880. Its hero is the self-made, diligent yeoman farmer. If he should fail it is because he has become lazy or drunk, or has forgotten his place in society:

There used to be a certain tacit agreement among all men that those who possessed capital, rank or reputation should be treated with courtesy. That courtesy did not imply that the landowner, the capitalist, or the minister of religion, was necessarily himself superior. But it did imply that those who administered property really represented the general order in which all were interested … These two characteristics, moral apathy and contempt of property – i.e. of social order – are probably exercising considerable influence in shaping the labourer’s future.

Jefferies grows shriller as he outlines the agents of these malign forces – the unemployed, the poachers, the publicans, the dispossessed and the dependant. Hodge himself, the ordinary labourer, remains invisible, except when Jefferies is rebuking him, in now familiar style, for his greed, bad cooking, lack of culture and laziness. How lucky he is, Jefferies remarks, only to work in the hours of daylight. After this, it is hard to take seriously the book’s closing note of regret about the insulting charity of the workhouse.

Yet alongside (and sometimes inside) these sour social commentaries he had begun writing short studies in natural history. They are lightly and sharply observed, and one senses Jefferies’ relief at having an escape route from the troubled world of human affairs. Wildlife in a Southern County was serialized in the Pall Mall Gazette during 1878, and its contents give some indication of what a versatile writer he was. There are pieces on orchards, woods, rabbits, ants, stiles, the ague, and ‘noises in the air’. The descriptions of the weather are especially convincing – perhaps because he saw this as one area which was beyond the corrupting influence of human society.

During this stage in his life his writing developed a characteristic discursiveness that was no doubt partly a result of his working as a jobbing journalist and having regularly to fill columns of a fixed length. Yet it was also a way of thinking. Many of the pieces are ramblings in an almost literal sense; anecdotes, observations, musings flit by as if they had been encountered and remarked upon during a walk.

In Round About a Great Estate (1880) this conversational style is employed to great effect and helps to make this the most unaffectedly charming of all Jefferies’ books. It is an ingenuous, buoyant collection of parish gossip, of characters and events that seem to have been chanced upon by accident. Yet it is celebratory rather than nostalgic. Jefferies remarks in his preface to the original edition:

In this book some notes have been made of the former state of things before it passes away entirely. But I would not have it therefore thought that I wish it to continue or return. My sympathies and hopes are with the light of the future, only I should like it to come from nature. The clock should be read by the sunshine, not the sun timed by the clock.

The worst thing that can be said about these natural history and documentary essays is not that they are inconsequential, but that they are impersonal and generalized. Even at his most perceptive, Jefferies viewed natural life with the same kind of detachment as he regarded the labourer. They aroused his curiosity but rarely his sympathy. But at the beginning of the 1880s a new intimacy starts to appear in his writing. He allows us to share specific experiences and deeply personal feelings. He seems, at last, to be engaged. A set of pieces on the fortunes of a trout trapped in a London brook, for instance, show us Jefferies in a very unfamiliar light – concerned, sentimental and increasingly aware of his own vulnerability.

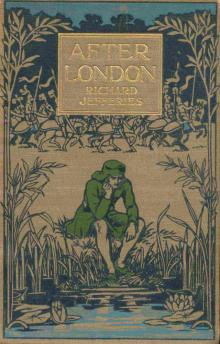

Much of this period, perhaps predictably, was taken up with escapist novels. Greene Ferne Farm (1880) is an old-fashioned pastoral with a dialect-speaking Chorus. Bevis (1882), a book for children, is set in Jefferies’ boyhood Wiltshire, which the young heroes transform into a fabulous playground for their fantasies. After London (1885) is a bitter vision of the collapse of urban civilization and of the city reclaimed by forest and swamp. Yet even with, so to speak, a clean slate, Jefferies still chooses to create a woodland feudal society, complete with reconstituted poachers as savages. There is some fine descriptive writing in his fiction (particularly in Amaryllis at the Fair, which is based on an idealized version of his own family), yet as novels they have to be regarded as failures. They have no real movement, either in the development of the plot or of the individual characters. David Garnett described Amaryllis as ‘a succession of stills, never a picture in motion’,* and Jefferies himself declared he would have been happy to have seen it published as ‘scenes of country life’ rather than as a novel.

During the early 1880s he was also working on his ‘soul-life’, a kind of spiritual autobiography that was published as The Story of My Heart in 1883. Like all mystical works this is comprehensible to the degree to which one shares the writer’s faith – which here is an intense pantheism. Yet the book is an account of a meditation rather than a complete religion. (Some of the short, rhythmical passages even read like mantras.) Typically Jefferies goes to a ‘thinking place’ – a tree, a stream, or more often the sea – lies under the sun and prays that he may have a revelation. He wishes to transcend the flesh, to transcend nature itself, though he cannot express what he wants, nor what, if anything, he has found. ‘The only idea I can give,’ he writes, ‘is that there is another idea.’ Yet if the mystical sections of The Story are typified by this kind of word-play – sincerely meant, no doubt, but meaningless – there is another strand of more earthly idealism in the book concerned with a belief in the perfectibility of man and the degradation of labour, themes that were to become increasingly prominent in his work.

Bevis: The Story of a Boy

Bevis: The Story of a Boy After London; Or, Wild England

After London; Or, Wild England Landscape with Figures

Landscape with Figures After London

After London