- Home

- Richard Jefferies

Bevis: The Story of a Boy Page 5

Bevis: The Story of a Boy Read online

Page 5

passedthe hawthorn under the may-bloom, Mark said, "Bevis," but Bevis did notanswer.

"Bevis," repeated Mark, "I have had enough now; stop, and you get in."

"I shall not," said Bevis. "You are a great story."

In another minute Mark spoke again:--

"Let me get out and tow you now." Bevis did not reply. "I say--I say--I say, Bevis."

No use. Bevis towed him the whole way, till the raft touched theshallow shore of the drinking-place. Then Mark got out and helped himdrag the vessel well up on the ground, so that it should not float away.

"Now," said Bevis, after it was quite done. "Will you be a story anymore?"

"No," said Mark, "I will not be a story again."

So they walked back side by side to the willow tree; Mark, who wasreally in the right, feeling in the wrong. At the tree Bevis picked upthe auger, and told him to bore the hole. Mark began, but suddenlystopped.

"What's the good of boring the hole when we have not got any gunpowder,"said he.

"No more we have," said Bevis. "This is very stupid, and they will notlet me have any, though I have got some money, and I have a great mindto buy some and hide it. Just as if we did not know how to use powder,and as if we did not know how to shoot! Oh, I know! We will go and cuta bough of alder--there's ever so many alders by the Longpond--and burnit and make charcoal; it makes the best charcoal, you know, and theyalways--use it for gunpowder, and then we can get some saltpetre. Letme see--"

"The Bailiff had some saltpetre the other day," said Mark.

"So he did: it is in the dairy. Oh yes, and I know where some sulphuris. It is in the garden-house, where the tools are, in the orchard;it's what they use to smother the bees with--"

"That's on brown paper," said Mark; "that won't do."

"No it's not. You have to melt it to put it on paper, and dip the paperin. This is in a piece, it is like a short bar, and we will pound it upand mix; them all together and make capital gunpowder."

"Hurrah!" cried Mark, throwing down the auger. "Let's go and cut thealder. Come on!"

"Stop," said Bevis. "Lean on me, and walk slow. Don't you know youhave caught a dreadful fever, from being in the swamps by the river, andyou can hardly walk, and you are very thin and weak? Lean on my arm andhang your head."

Mark hung his head, turning his rosy cheeks down to the buttercups, anddragged his sturdy fever-stricken limbs along with an effort.

"Humph!" said a gruff voice.

"It's the Indians!" cried Bevis, startled; for they were so absorbedthey had not heard the Bailiff come up behind them. They quite jumped,as if about to be scalped.

"What be you doing to that tree?" said the Bailiff.

"Find out," said Bevis. "It's not your tree: and why don't you say whenyou're coming?"

"I saw you from the hedge," said the Bailiff. "I was telling John whereto cut the bushes from for the new harrow." That caused the rustling inthe forest. "You'll never chop he down."

"That we shall, if we want to."

"No, you won't--he stops your ship."

"It isn't a ship: it's a raft."

"Well, you can't get by."

"That we can."

"I thinks you be stopped," said the Bailiff, having now looked at thetree more carefully. "He be main thick,"--with a certain sympathy forstolid, inanimate obstruction.

"I tell you, people like us are never stopped by anything," said Bevis."We go through forests, and we float down rivers, and we shoot tigers,and move the biggest trees ever seen--don't we, Mark?"

"Yes, that we do: nothing is anything to us."

"Of course not," said Bevis. "And if we can't chop it down or blow itup, as we mean to, then we dig round it. O, Mark, I say! I forgot!Let's dig a canal round it."

"How silly we were never to think of that!" said Mark. "A canal is thevery thing--from here to the creek."

He meant where the stream curved to enclose the Peninsula: the proposedcanal would make the voyage shorter.

"Cut some sticks--quick!" said Bevis. "We must plug out our canal--thatis what they always do first, whether it is a canal, or a railway, or adrain, or anything. And I must draw a plan. I must get my pocket-bookand pencil. Come on, Mark, and get the spade while I get my pencil."

Off they ran. The Bailiff leaned on his hazel staff, one hand againstthe willow, and looked down into the water, as calmly as the sun itselfreflected there. When he had looked awhile he shook his head andgrunted: then he stumped away; and after a dozen yards or so, glancedback, grunted, and shook his head again. It could not be done. Thetree was thick, the earth hard--no such thing: his sympathy, in a dullunspoken way, was with the immovable.

Mark went to work with the spade, throwing the turf he dug up into thebrook; while Bevis, lying at full length on the grass, drew his plan ofthe canal. He drew two curving lines parallel, and half an inch apart,to represent the bend of the brook, and then two, as straight as hecould manage, across, so as to shorten the distance, and avoid theobstruction. The rootlets of the grass held tight, when Mark tried tolift the spadeful he had dug, so that he could not tear them off.

He had to chop them at the side with his spade first, and then there wasa root of the willow in the way; a very obstinate stout root, for whichthe little hatchet had to be brought to cut it. Under the softer turfthe ground was very hard, as it had long been dry, so that by the timeBevis had drawn his plan and stuck in little sticks to show the coursethe canal was to take, Mark had only cleared about a foot square, andfour or five inches deep, just at the edge of the bank, where he couldthrust it into the stream.

"I have been thinking," said Bevis as he came back from the other end ofthe line, "I have been thinking what we are, now we are making thiscanal?"

"Yes," said Mark, "what are we?--they do not make canals on theMississippi. Is this the Suez canal?"

"Oh no," said Bevis. "This is not Africa; there is no sand, and thereare no camels about. Stop a minute. Put down that spade, don't diganother bit till we know what we are."

Mark put down the spade, and they both thought very hard indeed, lookingstraight at one another.

"I know," said Bevis, drawing a long breath. "We are digging a canalthrough Mount Athos, and we are Greeks."

"But was it the Greeks?" said Mark. "Are you sure--"

"Quite sure," said Bevis. "Perfectly quite sure. Besides, it doesn'tmatter. _We_ can do it if they did not, don't you see?"

"So we can: and who are you then, if we are Greeks?"

"I am Alexander the Great."

"And who am I!"

"O, you--you are anybody."

"But I _must_ be somebody," said Mark, "else it will not do."

"Well, you are: let me see--Pisistratus."

"Who was Pisistratus?"

"I don't know," said Bevis. "It doesn't matter in the least. Now dig."

Pisistratus dug till he came to another root, which Alexander the Greatchopped off for him with the hatchet. Pisistratus dug again anduncovered a water-rat's hole which went down aslant to the water. Theyboth knelt on the grass, and peered down the round tunnel: at the bottomwhere the water was, some of the fallen petals of the may-bloom had comein and floated there.

"This would do splendidly to put some gunpowder in and blow up, like theminers do," said Bevis. "And I believe that is the proper way to make acanal: it is how they make tunnels, I am sure."

"Greeks are not very good," said Mark. "I don't like Greeks: don'tlet's be Greeks any longer. The Mississippi was very much best."

"So it was," said Bevis. "The Mississippi is the nicest. I am notAlexander, and you are not Pisistratus. This is the Mississippi."

"Let us have another float down," said Mark. "Let me float down, and Iwill drag you all the way up this time."

"All right," said Bevis.

So they launched the raft, and Mark got in and floated down, and Beviswalked on the bank, giving him directions how to pilot the vessel, whichas before was brought up by t

he willow leaning over the water. Just asthey were preparing to tow it back again, and Bevis was climbing out onthe willow to get into the raft they heard a splashing down the brook.

"What's that?" said Mark. "Is it Indians?"

"No, it's an alligator. At least, I don't know. Perhaps it's a canoefull of Indians. Give me the pole, quick; there now, take

Bevis: The Story of a Boy

Bevis: The Story of a Boy After London; Or, Wild England

After London; Or, Wild England Landscape with Figures

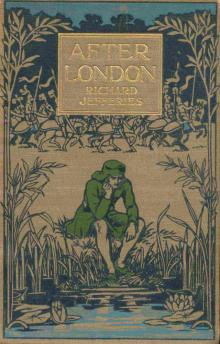

Landscape with Figures After London

After London