- Home

- Richard Jefferies

Landscape with Figures Page 4

Landscape with Figures Read online

Page 4

Over and above the actual cash wages of the labourer, which are now very good, must be reckoned his cottage and garden, and often a small orchard, at a nominal rent, his beer at his master’s expense, piece-work, gleaning after harvest, &c., which alter his real position very materially. In Gloucestershire, on the Cotswolds, the best-paid labourers are the shepherds, for in that great sheep-country much trust is reposed in them. At the annual auctions of shearlings which are held upon the large farms a purse is made for the shepherd of the flock, into which every one who attends is expected to drop a shilling, often producing £5. The shepherds on the Wiltshire Downs are also well paid, especially in lambing-time, when the greatest watchfulness and care are required. It has been stated that the labourer has no chance of rising from his position. This is sheer cant. He has very good opportunities of rising, and often does rise, to my knowledge. At this present moment I could mention a person who has risen from a position scarcely equal to that of a labourer, not only to have a farm himself, but to place his sons in farms. Another has just entered on a farm; and several more are on the high-road to that desirable consummation. If a labourer possesses any amount of intelligence he becomes head-carter or head-fagger, as the case may be; and from that to be assistant or under-bailiff, and finally bailiff. As a bailiff he has every opportunity to learn the working of a farm, and is often placed in entire charge of a farm at a distance from his employer’s residence. In time he establishes a reputation as a practical man, and being in receipt of good wages, with very little expenditure, saves some money. He has now little difficulty in obtaining the promise of a farm, and with this can readily take up money. With average care he is a made man. Others rise from petty trading, petty dealing in pigs and calves, till they save sufficient to rent a small farm, and make that the basis of larger dealing operations. I question very much whether a clerk in a firm would not find it much more difficult, as requiring larger capital, to raise himself to a level with his employer than an agricultural labourer does to the level of a farmer.

Many labourers now wander far and wide as navvies, &c., and perhaps when these return home, as most of them do, to agricultural labour, they are the most useful and intelligent of their class, from a readiness they possess to turn their hand to anything. I know one at this moment who makes a large addition to his ordinary wages by brewing for the small inns, and very good liquor he brews, too. They pick up a large amount of practical knowledge.

The agricultural women are certainly not handsome; I know no peasantry so entirely uninviting. Occasionally there is a girl whose nut-brown complexion and sloe-black eyes are pretty, but their features are very rarely good, and they get plain quickly, so soon as the first flush of youth is past. Many have really good hair in abundance, glossy and rich, perhaps from its exposure to the fresh air. But on Sundays they plaster it with strong-smelling pomade and hair-oil, which scents the air for yards most unpleasantly. As a rule, it may safely be laid down that the agricultural women are moral, far more so than those of the town. Rough and rude jokes and language are, indeed, too common; but that is all. No evil comes of it. The fairs are the chief cause of immorality. Many an honest, hard-working servant-girl owes her ruin to these fatal mops and fairs, when liquor to which she is unaccustomed overcomes her. Yet it seems cruel to take from them the one day or two of the year on which they can enjoy themselves fairly in their own fashion. The spread of friendly societies, patronized by the gentry and clergy, with their annual festivities, is a remedy which is gradually supplying them with safer, and yet congenial, amusement. In what may be termed lesser morals I cannot accord either them or the men the same praise. They are too ungrateful for the many great benefits which are bountifully supplied them – the brandy, the soup, and fresh meat readily extended without stint from the farmer’s home in sickness to the cottage are too quickly forgotten. They who were most benefited are often the first to most loudly complain and to backbite. Never once in all my observation have I heard a labouring man or woman make a grateful remark; and yet I can confidently say that there is no class of persons in England who receive so many attentions and benefits from their superiors as the agricultural labourers. Stories are rife of their even refusing to work at disastrous fires because beer was not immediately forth-coming. I trust this is not true; but it is too much in character. No term is too strong in condemnation for those persons who endeavour to arouse an agitation among a class of people so short-sighted and so ready to turn against their own benefactors and their own interest. I am credibly informed that one of these agitators, immediately after the Bishop of Gloucester’s unfortunate but harmlessly intended speech at the Gloucester Agricultural Society’s dinner – one of these agitators mounted a platform at a village meeting and in plain language incited and advised the labourers to duck the farmers! The agricultural women either go out to field-work or become indoor servants. In harvest they hay-make – chiefly light work, as raking – and reap, which is much harder labour; but then, while reaping they work their own time, as it is done by the piece. Significantly enough, they make longer hours while reaping. They are notoriously late to arrive, and eager to return home, on the hay-field. The children help both in haymaking and reaping. In spring and autumn they hoe and do other piece-work. On pasture farms they beat clots or pick up stones out of the way of the mowers’ scythes. Occasionally, but rarely now, they milk. In winter they wear gaiters, which give the ankles a most ungainly appearance. Those who go out to service get very low wages at first from their extreme awkwardness, but generally quickly rise. As dairy-maids they get very good wages indeed. Dairymaids are scarce and valuable. A dairymaid who can be trusted to take charge of a dairy will sometimes get £20 besides her board (liberal) and sundry perquisites. These often save money, marry bailiffs, and help their husbands to start a farm.

In the education provided for children Wiltshire compares favourably with other counties. Long before the passing of the recent Act in reference to education the clergy had established schools in almost every parish, and their exertions have enabled the greater number of places to come up to the standard required by the Act, without the assistance of a School Board. The great difficulty is the distance children have to walk to school, from the sparseness of population and the number of outlying hamlets. This difficulty is felt equally by the farmers, who, in the majority of cases, find themselves situated far from a good school. In only one place has anything like a cry for education arisen, and that is on the extreme northern edge of the county. The Vice-Chairman of the Swindon Chamber of Agriculture recently stated that only one-half of the entire population of Inglesham could read and write. It subsequently appeared that the parish of Inglesham was very sparsely populated, and that a variety of circumstances had prevented vigorous efforts being made. The children, however, could attend schools in adjoining parishes, not farther than two miles, a distance which they frequently walk in other parts of the country.

Those who are so ready to cast every blame upon the farmer, and to represent him as eating up the earnings of his men and enriching himself with their ill-paid labour, should remember that farming, as a rule, is carried on with a large amount of borrowed capital. In these days, when £6 an acre has been expended in growing roots for sheep, when the slightest derangement of calculation in the price of wool, meat, or corn, or the loss of a crop, seriously interferes with a fair return for capital invested, the farmer has to sail extremely close to the wind, and only a little more would find his canvas shaking. It was only recently that the cashier of the principal bank of an agricultural county, after an unprosperous year, declared that such another season would make almost every farmer insolvent. Under these circumstances it is really to be wondered at that they have done as much as they have for the labourer in the last few years, finding him with better cottages, better wages, better education, and affording him better opportunities of rising in the social scale. – I am, Sir, faithfully yours,

RICHARD JEFFERIES

COATE FARM, S

WINDON, Nov. 12, 1872

The Labourer’s Daily Life

First published in Fraser’s Magazine, November 1874

First collected in The Toilers of the Field, 1892

Many labourers can trace their descent from farmers or well-to-do people, and it is not uncommon to find here and there a man who believes that he is entitled to a large property in Chancery, or elsewhere, as the heir. They are very fond of talking of these things, and naturally take a pride in feeling themselves a little superior in point of ancestry to the mass of labourers.

How this descent from a farmer to a labourer is managed there are at this moment living examples going about the country. I knew a man who for years made it the business of his life to go round from farm to farm soliciting charity, and telling a pitiful tale of how he had once been a farmer himself. This tale was quite true, and as no class likes to see their order degraded, he got a great deal of relief from the agriculturists where he was known. He was said to have been wild in his youth, and now in his old age was become a living representative of the farmer reduced to a labourer.

This reduction is, however, usually a slow process, and takes two generations to effect – not two generations of thirty years each, but at least two successors in a farm.

Perhaps the decline of a farming family began in an accession of unwonted prosperity. The wheat or the wool went up to a high price, and the farmer happened to be fortunate and possessed a large quantity of those materials. Or he had a legacy left him, or in some way or other made money by good fortune rather than hard work. This elated his heart, and thinking to rise still higher in life, he took another, or perhaps two more large farms. But to stock these required more money than he could produce, and he had to borrow a thousand or so. Then the difficulty of attending to so large an acreage, much of it distant from his home, made it impossible to farm in the best and most profitable manner. By degrees the interest on the loan ate up all the profit on the new farms. Then he attempted to restore the balance by violent high farming. He bought manures to an unprecedented extent, invested in costly machinery – anything to produce a double crop. All this would have been very well if he had had time to wait till the grass grew; but meantime the steed starved. He had to relinquish the additional farms, and confine himself to the original one with a considerable loss both of money and prestige. He had no energy to rise again; he relapsed into slow, dawdling ways, perpetually regretting and dwelling on the past, yet making no effort to retrieve it.

This is a singular and strongly marked characteristic of the agricultural class, taken generally. They work and live and have their being in grooves. So long as they can continue in that groove, and go steadily forward, without much thought or trouble beyond that of patience and perseverance, all goes well; but if any sudden jolt should throw them out of this rut, they seem incapable of regaining it. They say, ‘I have lost my way; I shall never get it again.’ They sit down and regret the past, granting all their errors with the greatest candour; but the efforts they make to regain their position are feeble in the extreme.

So our typical unfortunate farmer folds his hands, and in point of fact slumbers away the rest of his existence, content with the fireside and a roof over his head, and a jug of beer to drink. He does not know French, he has never heard of Metternich, but he puts the famous maxim in practice, and, satisfied with to-day, says in his heart, Après nous le Déluge. No one disturbs him; his landlord has a certain respect and pity for him – respect, perhaps, for an old family that has tilled his land for a century, but which he now sees is slowly but irretrievably passing away. So the decayed farmer dozes out his existence.

Meantime his sons are coming on, and it too often happens that the brief period of sunshine and prosperity has done its evil work with them too. They have imbibed ideas of gentility and desire for excitement utterly foreign to the quiet, peaceful life of an agriculturist. They have gambled on the turf and become involved. Notwithstanding the fall of their father from his good position, they still retain the belief that in the end they shall find enough money to put all to rights; but when the end comes there is a deficiency. Among them there is perhaps one more plodding than the rest. He takes the farm, and keeps a house for the younger children. In ten years he becomes a bankrupt, and the family are scattered abroad upon the face of the earth. The plodding one becomes a bailiff, and lives respectably all his life; but his sons are never educated, and he saves no money; there is nothing for them but to go out to work as farm labourers.

Such is something like the usual way in which the decline and fall of a farming family takes place, though it may of course arise from unforeseen circumstances, quite out of the control of the agriculturist. In any case the children graduate downwards till they become labourers. Nowadays many of them emigrate, but in the long time that has gone before, when emigration was not so easy, many hundreds of families have thus become reduced to the level of the labourers they once employed. So it is that many of the labourers of to-day bear names which less than two generations ago were well known and highly respected over a wide tract of country. It is natural for them to look back with a certain degree of pleasure upon that past, and some may even have been incited to attempt to return to the old position.

But the great majority, the mass, of the agricultural labourers have been labourers time out of mind. Their fathers were labourers, their grandfathers and their great-grandfathers have all worked upon the farms, and very often almost continuously during that long period of time upon the farms in one parish. All their relations have been, and still are, labourers, varied by one here who has become a tinker, or one there who keeps a small roadside beerhouse. When this is the case, when a man and all his ancestors for generations have been hewers of wood and drawers of water, it naturally follows that the present representative of the family holds strongly to the traditions, the instincts, acquired during the slow process of time. What those instincts are will be better gathered from a faithful picture of his daily life.

Most of the agricultural labourers are born in a thatched cottage by the roadside, or in some narrow lane. This cottage is usually an encroachment. In the olden time, when land was cheap, and the competition for it dull, there were many strips and scraps which were never taken any notice of, and of which at this hour no record exists either in the parochial papers or the Imperial archives. Probably this arose from the character of the country in the past, when the greater part was open, or, as it was called, champaign land, without hedge, or ditch, or landmark. Near towns a certain portion was enclosed generally by the great landowners, or for the use of the tradesmen. There was also a large enclosure called the common land, on which all burgesses or citizens had a right to feed so many cattle, sheep, or horses. As a rule the common land was not enclosed by hedges in fields, though instances do occur in which it was. There were very few towns in the reign of Charles II that had not got their commons attached to them; but outside and beyond these patches of cultivation round the towns the country was open, unenclosed, and the boundaries ill-defined. The king’s highway ran from one point to another, but its course was very wide. Roads were not then macadamized and strictly confined to one line. The want of metalling, and the consequent fearful ruts and sloughs, drove vehicles and travellers further and further from what was the original line, till they formed a track perhaps a score or two of yards wide. When fields became more generally enclosed it was still only in patches, and these strips and spaces of green sward were left utterly uncared for and unnoticed. These were encamped upon by the gipsies and travelling folk, and their unmolested occupation no doubt suggested to the agricultural labourer that he might raise a cottage upon such places, or cultivate it for his garden.

Bevis: The Story of a Boy

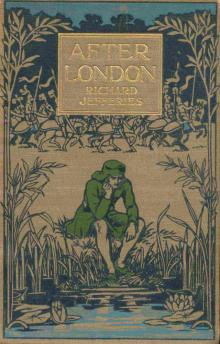

Bevis: The Story of a Boy After London; Or, Wild England

After London; Or, Wild England Landscape with Figures

Landscape with Figures After London

After London