- Home

- Richard Jefferies

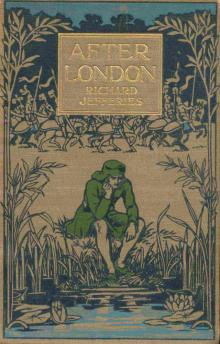

After London; Or, Wild England Page 2

After London; Or, Wild England Read online

Page 2

CHAPTER II

WILD ANIMALS

When the ancients departed, great numbers of their cattle perished. Itwas not so much the want of food as the inability to endure exposurethat caused their death; a few winters are related to have so reducedthem that they died by hundreds, many mangled by dogs. The hardiest thatremained became perfectly wild, and the wood cattle are now moredifficult to approach than deer.

There are two kinds, the white and the black. The white (sometimes dun)are believed to be the survivors of the domestic roan-and-white, for thecattle in our enclosures at the present day are of that colour. Theblack are smaller, and are doubtless little changed from their state inthe olden times, except that they are wild. These latter are timid,unless accompanied by a calf, and are rarely known to turn upon theirpursuers. But the white are fierce at all times; they will not, indeed,attack man, but will scarcely run from him, and it is not always safe tocross their haunts.

The bulls are savage beyond measure at certain seasons of the year. Ifthey see men at a distance, they retire; if they come unexpectedly faceto face, they attack. This characteristic enables those who travelthrough districts known to be haunted by white cattle to provide againstan encounter, for, by occasionally blowing a horn, the herd that may bein the vicinity is dispersed. There are not often more than twenty in aherd. The hides of the dun are highly prized, both for their intrinsicvalue, and as proofs of skill and courage, so much so that you shallhardly buy a skin for all the money you may offer; and the horns arelikewise trophies. The white or dun bull is the monarch of our forests.

Four kinds of wild pigs are found. The most numerous, or at least themost often seen, as it lies about our enclosures, is the commonthorn-hog. It is the largest of the wild pigs, long-bodied andflat-sided, in colour much the hue of the mud in which it wallows. Tothe agriculturist it is the greatest pest, destroying or damaging allkinds of crops, and routing up the gardens. It is with difficulty keptout by palisading, for if there be a weak place in the wooden framework,the strong snout of the animal is sure to undermine and work a passagethrough.

As there are always so many of these pigs round about inhabited placesand cultivated fields, constant care is required, for they instantlydiscover an opening. From their habit of haunting the thickets and bushwhich come up to the verge of the enclosures, they have obtained thename of thorn-hogs. Some reach an immense size, and they are veryprolific, so that it is impossible to destroy them. The boars are fierceat a particular season, but never attack unless provoked to do so. Butwhen driven to bay they are the most dangerous of the boars, on accountof their vast size and weight. They are of a sluggish disposition, andwill not rise from their lairs unless forced to do so.

The next kind is the white hog, which has much the same habits as theformer, except that it is usually found in moist places, near lakes andrivers, and is often called the marsh-pig. The third kind is perfectlyblack, much smaller in size, and very active, affording by far the bestsport, and also the best food when killed. As they are found on thehills where the ground is somewhat more open, horses can follow freely,and the chase becomes exciting. By some it is called the hill-hog, fromthe locality it frequents. The small tusks of the black boar are usedfor many ornamental purposes.

These three species are considered to be the descendants of the variousdomestic pigs of the ancients, but the fourth, or grey, is thought to bethe true wild boar. It is seldom seen, but is most common in thesouth-western forests, where, from the quantity of fern, it is calledthe fern-pig. This kind is believed to represent the true wild boar,which was extinct, or merged in the domestic hog among the ancients,except in that neighbourhood where the strain remained.

With wild times, the wild habits have returned, and the grey boar is atonce the most difficult of access, and the most ready to encountereither dogs or men. Although the first, or thorn-hog, does the mostdamage to the agriculturist because of its numbers, and its habit ofhaunting the neighbourhood of enclosures, the others are equallyinjurious if they chance to enter the cultivated fields.

The three principal kinds of wild sheep are the horned, the thyme, andthe meadow. The thyme sheep are the smallest, and haunt the highesthills in the south, where, feeding on the sweet herbage of the ridges,their flesh is said to acquire a flavour of wild thyme. They move insmall flocks of not more than thirty, and are the most difficult toapproach, being far more wary than deer, so continuously are they huntedby the wood-dogs. The horned are larger, and move in greater numbers; asmany as two hundred are sometimes seen together.

They are found on the lower slopes and plains, and in the woods. Themeadow sheep have long shaggy wool, which is made into various articlesof clothing, but they are not numerous. They haunt river sides, and theshores of lakes and ponds. None of these are easily got at, on accountof the wood-dogs; but the rams of the horned kind are reputed tosometimes turn upon the pursuing pack, and butt them to death. In theextremity of their terror whole flocks of wild sheep have been drivenover precipices and into quagmires and torrents.

Besides these, there are several other species whose haunt is local. Onthe islands, especially, different kinds are found. The wood-dogs willoccasionally, in calm weather, swim out to an island and kill everysheep upon it.

From the horses that were in use among the ancients the two wild speciesnow found are known to have descended, a fact confirmed by their evidentresemblance to the horses we still retain. The largest wild horse isalmost black, or inclined to a dark colour, somewhat less in size thanour present waggon horses, but of the same heavy make. It is, however,much swifter, on account of having enjoyed liberty for so long. It iscalled the bush-horse, being generally distributed among thickets andmeadow-like lands adjoining water.

The other species is called the hill-pony, from its habitat, the hills,and is rather less in size than our riding-horse. This latter is shortand thick-set, so much so as not to be easily ridden by short personswithout high stirrups. Neither of these wild horses are numerous, butneither are they uncommon. They keep entirely separate from each other.As many as thirty mares are sometimes seen together, but there aredistricts where the traveller will not observe one for weeks.

Tradition says that in the olden times there were horses of a slenderbuild whose speed outstripped the wind, but of the breed of these famousracers not one is left. Whether they were too delicate to withstandexposure, or whether the wild dogs hunted them down is uncertain, butthey are quite gone. Did but one exist, how eagerly it would be soughtout, for in these days it would be worth its weight in gold, unless,indeed, as some affirm, such speed only endured for a mile or two.

It is not necessary, having written thus far of the animals, thatanything be said of the birds of the woods, which every one knows werenot always wild, and which can, indeed, be compared with such poultry asare kept in our enclosures. Such are the bush-hens, the wood-turkeys,the galenae, the peacocks, the white duck and the white goose, all ofwhich, though now wild as the hawk, are well known to have been oncetame.

There were deer, red and fallow, in numerous parks and chases of veryold time, and these, having got loose, and having such immense tracts toroam over unmolested, went on increasing till now they are beyondcomputation, and I have myself seen a thousand head together. Withinthese forty years, as I learn, the roe-deer, too, have come down fromthe extreme north, so that there are now three sorts in the woods.Before them the pine-marten came from the same direction, and, thoughthey are not yet common, it is believed they are increasing. For thefirst few years after the change took place there seemed a danger lestthe foreign wild beasts that had been confined as curiosities inmenageries should multiply and remain in the woods. But this did nothappen.

Some few lions, tigers, bears, and other animals did indeed escape,together with many less furious creatures, and it is related that theyroamed about the fields for a long time. They were seldom met with,having such an extent of country to wander over, and after a whileentirely disappeared. If any progeny were born, the winte

r frosts musthave destroyed it, and the same fate awaited the monstrous serpentswhich had been collected for exhibition. Only one such animal now existswhich is known to owe its origin to those which escaped from the dens ofthe ancients. It is the beaver, whose dams are now occasionally foundupon the streams by those who traverse the woods. Some of the aquaticbirds, too, which frequent the lakes, are thought to have beenoriginally derived from those which were formerly kept as curiosities.

In the castle yard at Longtover may still be seen the bones of anelephant which was found dying in the woods near that spot.

Bevis: The Story of a Boy

Bevis: The Story of a Boy After London; Or, Wild England

After London; Or, Wild England Landscape with Figures

Landscape with Figures After London

After London